As Cory Doctorow, the Canadian writer and novelist has so often pointed out, the original democratic promise of the early internet has been squandered, co-opted by parasitic rentier capitalism.

What was once a loosely federated network for sharing, tinkering, and building has hardened into a set of closed platforms optimized for extraction—of attention, of data, and, increasingly, of money. The contemporary web is not primarily about learning or collaboration. It is about capture. This is not an accident. It is the result of incentives baked into platform capitalism, and higher education has largely adapted itself to those incentives rather than resisting them.

It did not have to be this way.

When I was a middle-school student in the 1990s, I fell in love with the internet in a very different form. I was part of a thriving community organized around NHL 95, a hockey video game whose longevity depended almost entirely on user creativity. We exchanged custom rosters, graphics hacks, and commentary files. None of this was polished. None of it was monetized. Much of it lived on Geocities pages that looked terrible and worked imperfectly—but it worked. You downloaded someone else’s labor, credited them, modified it, and shared it back out again.

That was the internet I learned on: writing, sharing, linking, downloading, and iterating. No feeds. No algorithms. No engagement metrics. Just people making things for each other.

Historians have made similar observations at scale. Roy Rosenzweig, writing about Wikipedia in the mid-2000s, recognized both its dangers and its radical promise. Wikipedia was not valuable because it was perfect—it wasn’t—but because it demonstrated that knowledge production could be collaborative, iterative, and broadly accessible without requiring either institutional gatekeeping or commercial intermediaries. Its core innovation was not accuracy alone, but attribution and revision: the ability to see who contributed what, and to improve upon it over time.

MYOTextbook emerges from that lineage.

The project began with a simple frustration: I wanted to create course readers that were affordable (ideally free), accessible to all students, and adaptable over time. Existing solutions—commercial textbooks, static PDFs, proprietary “inclusive access” platforms—failed on at least one of those criteria, and usually on all three. Tools like Wikipedia’s Book Creator gestured toward a solution, but stopped short of something instructors could truly own and iterate on.

So I built one.

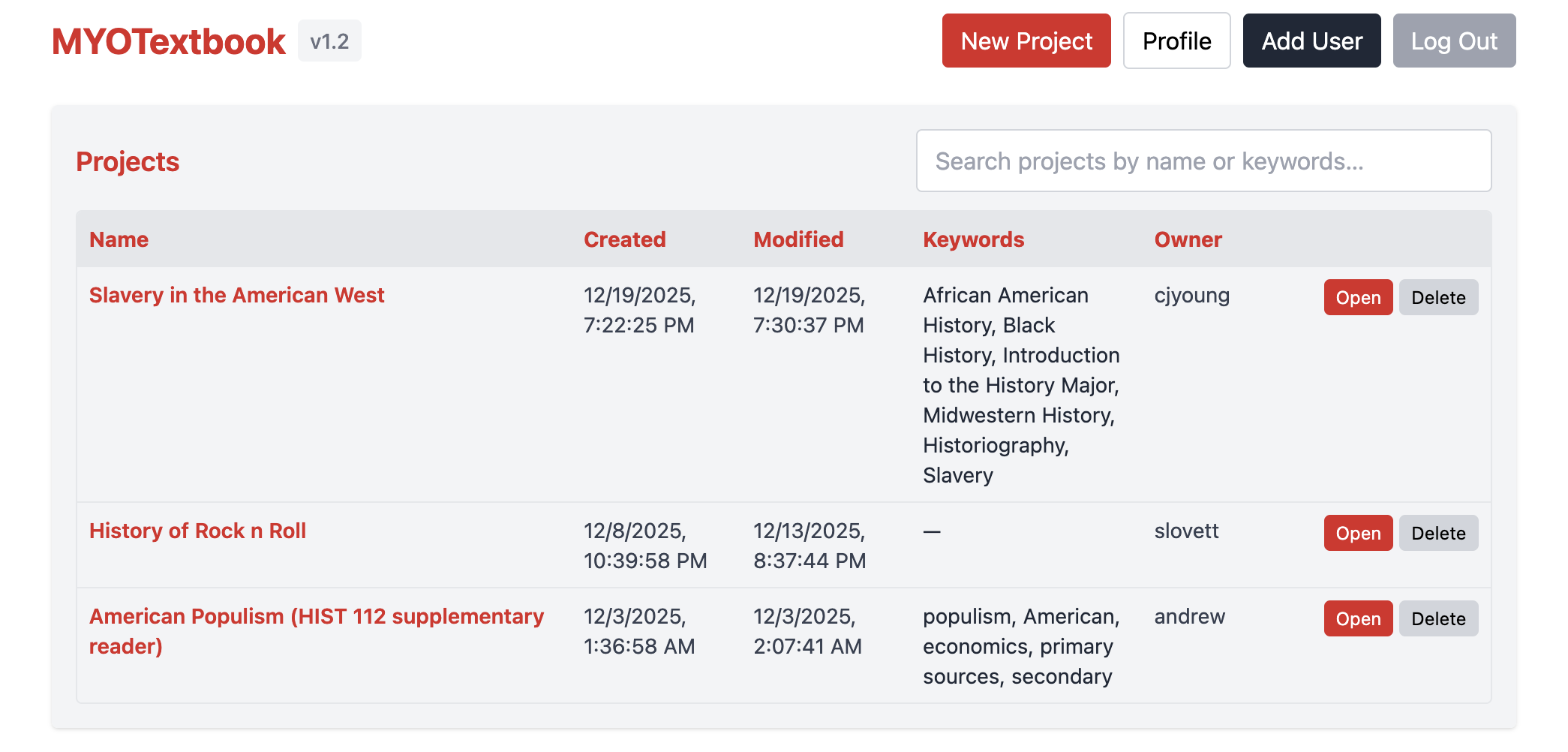

MYOTextbook is an open-source application that allows instructors to assemble course readers from a mix of sources—Wikipedia entries, public websites, locally held PDFs and DOCX files, and images—and export them as PDF, EPUB, or Markdown documents. Under the hood, it relies on familiar, well-maintained open source tools: Node.js, Express, SQLite, Pandoc, and Tectonic. The choices here are deliberate. These are not flashy technologies. I used LLMs (mostly Anthropic’s Sonnet) to improve the code and to help me when I ran into problems. The technologies used are stable, interoperable, and–most importantly–open. Anyone that is interested can check out MYOText here. You can request a username and password through the Profile menu. (GitHub here too!)

The outputs matter too. EPUB and Markdown are not afterthoughts; they are central. These formats allow the created readers to be Title-II compliant and accessible to students using screen readers, text-to-speech tools, or alternative display devices. They also allow students to annotate, remix, and retain materials after the course ends—something most proprietary platforms actively prevent.

But MYOTextbook is not just about access. It is about iteration with attribution.

Instructors can share readers with one another, comment on them, revise them, and improve them collaboratively while maintaining clear credit both to the instructor-authors and to the original creators of collected sources. This is not content scraping. It is scholarly assembly. The goal is a democracy of data in which teaching materials improve over time through use, critique, and revision—much like open-source software or the best moments of the early web.

This is, unapologetically, a rejection of the current trajectory of educational technology. Students should not pay hundreds of dollars for static content locked behind DRM. Instructors should not be forced into closed ecosystems that prevent sharing or revision. And accessibility should not be an optional add-on negotiated after the fact.

The old internet was imperfect, messy, and fragile. But it was oriented toward sharing rather than capture. MYOTextbook is an attempt—modest, practical, and deliberately unglamorous—to recover some of that ethos for higher education. Not as nostalgia, but as infrastructure.

If the democratic promise of the internet has been squandered, it is not gone. It is just buried under layers of platforms we can choose not to use. In addition to recommending that people use these monopolistic parasite web platforms less, I hope this small addition to the educators’ tool set can be helpful.

Leave a Reply